Article: Fixing our energy

-

Share This:

- Description

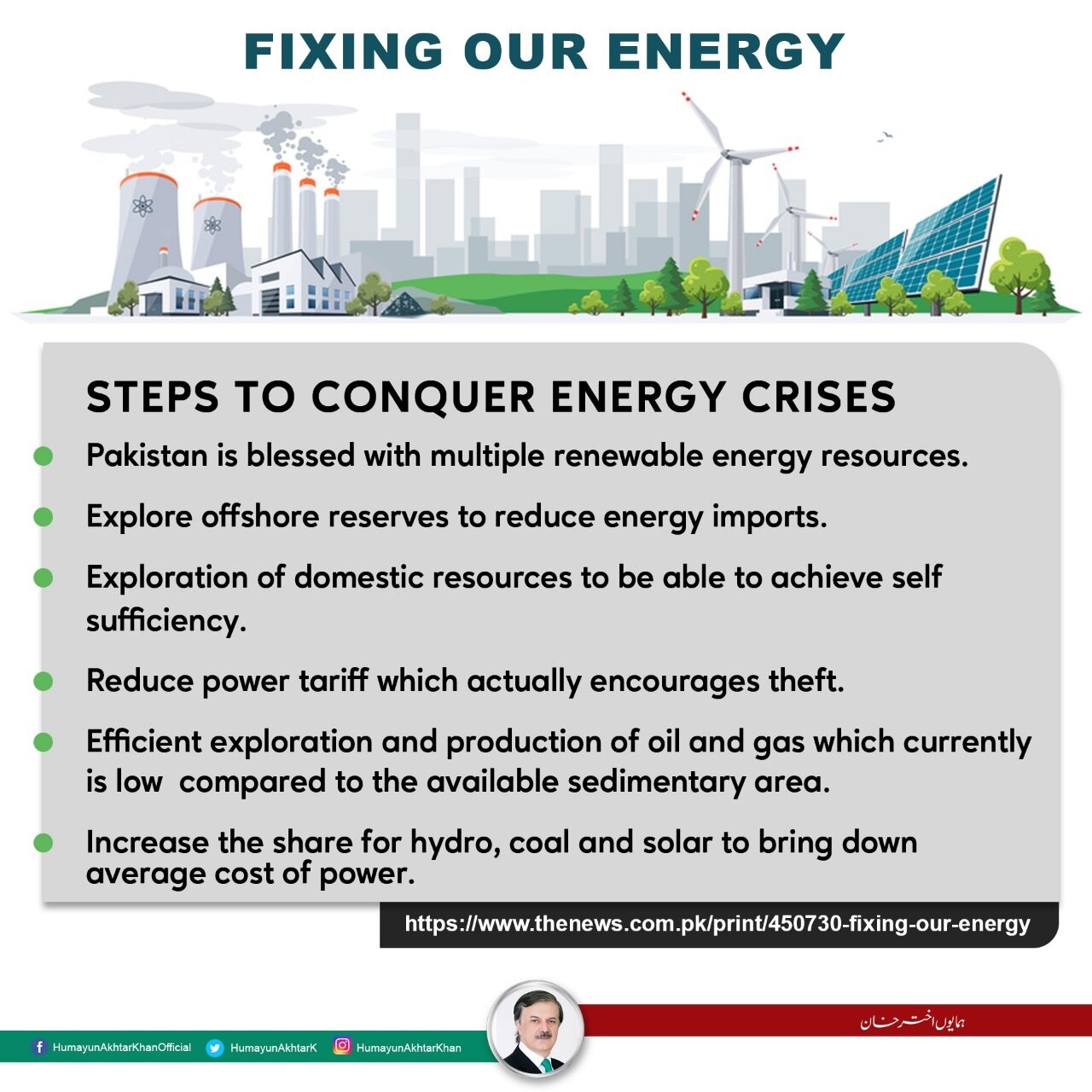

- It seems that the warnings about the frailty of our energy supply are mostly true. And though successive governments have pledged to fix the sector, it is still where it was three decades ago. Only, a bit worse. As before, we still depend considerably on imported fuel, straining our usually modest forex reserves. The price of fuel is subject to the volatility of supply and demand as well as of geopolitics. Available energy stock is usually meagre, which may have been a concern during the recent crisis on the eastern border. Defying economic logic, while the price of electric power is high, it is still in short supply. This is because the policy for power generation is flawed. Revenue loss from weak governance and theft is massive, over 26 percent of all power. Estimates of financial loss range between Rs150 billion and Rs200 billion. Resultantly, the system cannot recover costs. The government says that a dysfunctional power sector pre-empts large budget resources in subsidy. It is possible that much of it indirectly funds the generous incentives for private power production. We must correct the fundamental issues that plague power supply. A new development that has become more pronounced in the last decade is loss in transmission of gas. Some estimate the loss to be Rs50 billion a year. In fact, energy and power theft has shadowed us with bull-headed tenacity. The test of a reliable energy supply chain lies in how it services consumers. Unreliable power supply still constrains industrial growth and exasperates consumers. Loadshedding, high prices and faulty billing are conditions that we have learned to accept. Despite major increase in LNG import, gas supply is uncertain and costly. Gas distributors add an estimated 40 percent premium to the input cost of gas. This is unreasonably high. There is much for the government to do to set right decades of accumulated wrong. Many areas need correction, though why they have not been dealt with by successive governments is baffling. Estimates of cost to the economy from energy shortage vary, though 2.5 percent of GDP is the accepted figure. This equals a whopping Rs875 billion a year. Shortage slows economic activity, retards competitiveness and hampers growth. It doesn’t have to be this way. Pakistan is blessed with large conventional and renewable resources. Over the years, the country has also built a reasonable stock of infrastructure for supply of energy and power. Thousands of kilometres of electric wiring and oil and gas pipelines link many million consumers. Yet, about 30 percent of the population, or 60 million people, do not have electricity. More than 50 percent of Pakistanis rely on biomass as cooking fuel. Forests are subject to slash and burn. The reality is that the problem of Pakistan’s energy sector is not about availability of resources but about weak policies and management. Overall, the government of Pakistan has been found wanting in its ability to frame and regulate energy and power policy. Because of generous incentives, the Private Power Policy, 1994 and its later editions have made power costly to produce. Its implementation has not favoured efficiency or better fuel mix. In fact, by encouraging imports, it deterred development of energy resources. We must embark at once on a comprehensive plan for a viable and sustainable energy and power sectors. To begin with, it is necessary to establish energy demand and then determine the desired energy mix, optimising between the goals of affordability, environment, technical viability, and reliability. It is important also for the government to implement its energy efficiency plans. Savings from it could equal 2,250 MW in generation capacity. Above all, the plan must have a financing model to take care of the large capital need. The Petroleum Institute Pakistan or PIP estimates that Pakistan’s 2017 energy deficit was 10 million tonne oil equivalent. This is in addition to the 72 MTOE available that year, including 34.5 MTOE imports. PIP estimates that with GDP growth of about 5.5 percent annually, our energy needs would be about 230 MTOE in 2030. Of this, they estimate import will be about 45 percent, nearly $50 billion. Offshore findings, if confirmed, would reduce imports. Even within imported energy, geopolitics has restrained us from the cheaper option of piped gas from Iran or Turkmenistan. It now seems that Central Asian energy, though still available, is lost opportunity, as the region is now connected widely with other economies. There are several options to indigenise energy supply. In addition to offshore energy, Pakistan’s shale resources are high. However, there are major financial and technical challenges in that, especially at the present world energy prices. Tight gas is a possibility. Its exploration has begun. The government may review the policy framework for tight gas to fast track realisation of the estimated 35 billion barrels of reserves that exist. Overall, exploration and production of oil and gas is very low compared to the available sedimentary area. We also have large coal deposits in Thar. Yet, environmental concerns and the unproven clean coal technology is a constraint. Most important, we have realised only a part of the massive hydro potential. Though initial capital cost is high, hydro energy has great potential. In addition, with costs coming down, solar and wind too are attractive energy sources. Moving to electric power, there is much to do here also. Focus on generation has caused imbalance between power production, transmission and distribution. We do not have enough capacity to disseminate the power produced. The inability to recover costs has starved the power supply chain of resources, limiting investment. Yet, increase in tariff alone is not enough. Higher tariff is an incentive for more theft. Also, it dampens demand and is unfair on paying consumers. We must take strict administrative action to plug revenue loss. Also, we must immediately act to increase the share for hydro, coal and solar to bring down average cost of power. The writer was commerce minister from 2002 till 2007. He is chair and CEO of the Institute for Policy Reforms.

- Updated:

- 3/30/2019 12:00:00 AM